See also The_Netherlands_from_1600_to_the_1820s

You may also wish to read The Danish and Dutch Settlements on Amager Island: Four Hundred ‘Years of SocioCultural Interaction by ROBERT T. ANDERSON, Centre National La Recherche Scientijique.

Here’s an excerpt from the book:

THE COLONIZATION

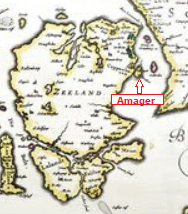

Denmark is a nation of some five hundred islands plus the peninsula of Jutland. One of the many islands is Amager. Small (65 sq. km.) and flat, it is separated by a narrow strait from Copenhagen, located on Sealand, the largest of the Danish islands. The story of the Dutch colony on Amager begins with a love affair. While still crown prince, Christian I fell in love with Dyveke, an exile from North Holland whom he met while sojourning in the Norwegian provinces. In 1513, after ascending the throne, Christian brought Dyveke and her mother, known as “Mother Sigbrit,” to Copenhagen, giving them a house in the capital as well as a summer residence on Amager. Through his love for the daughter, Christian came under the influence of Mother Sigbrit, a forceful woman who had a hand in many events in his reign, including, it seems quite certain, the negotiations that brought immigrants to Amager from North Holland. The Dutch were invited to settle in Denmark because their skill and advanced techniques in agriculture and dairying would enable them to supply the court and the capital with high quality vegetables, butter, and cheese. Mother Sigbrit was apparently quick to see that the island of Amager, flat, fertile, and convenient to Copenhagen, was well suited to Dutch techniques, and because it was the private property of the king it could be made available. In 1515 Christian issued his earliest invitation to the Netherlands. In 1516 a few Dutchmen came to Denmark, presumably to inspect personally the land being offered them.

Late in 1520 the colony came, 184 people comprising 24 families. In a letter of privileges granted in 1521, King Christian I1 gave the immigrants all of the island of Amager, excepting the royal fishing camp at Dragor but including the neighboring island of Saltholm; the utility of the latter was limited by its seasonal inundation. Although much of Amager lay unused, the 736 Danish inhabitants were told to turn over their farms to the newcomers. However, the situation remained fluid for a number of years. Before all of the Danes were evacuated, Christian I1 was forced to flee the country and was replaced on the throne in 1523 by his uncle, Frederik I, who lacked special interest in the Dutch. In 1541, twenty years after the Dutch first came, the situation was crystallized by the issuance of a royal letter of protection which affirmed the Danish farmers’ rights to their farms on northern Amager as well as their equal rights with the Dutch to use the meadows, chalk deposits, and fishing grounds of Saltholm. Many of the farms were returned to the original owners, and although in 1547 Frederik’s successor, Christian 111, reaffirmed the privileges of the Dutch essentially as they were originally given in 1521, the practical effect was that the immigrants were confined to the southern part of the island, leaving the northern part to the original inhabitants. The center of the colony was ancient Søndre Magleby, a village of about twenty farms. Renamed Store Magleby (Dutch, Grote Maglebeu), it was much changed in order to satisfy the newcomers’ needs for land distribution and was completely rebuilt after suffering destruction in the Count’s Feud (1533-36).

THE IMMIGRANT DUTCH AMAGERIANS

The land was the private property of the colonists. As stated in the original letter of privileges and reaffirmed by Christian III, the Dutch were free to divide the land among themselves, to sell it, and to give it in inheritance, all according to Dutch customs. The only restriction on ownership, other than the requirement to pay taxes, was that if a family died out completely the land was to revert to the crown, but with the proviso that it was then to be auctioned off by the village head to the highest bidder, who was always a Dutchman. In accordance with these privileges, the 24 families divided the land into 24 farms of from 35 to 40 acres each. The rest of the land was used in common; each farmer had the use of grazing areas in proportion to the amount of his land kept under the plow, the total amount of land available to each of the original farms being approximately 135 acres. With the passage of time and the division of farms by inheritance and sale, the land became parcelled into many small plots, a single farmer having as many as 30 or 40 separate strips. The farms also became unequal in size and value. The royal privileges included the right to local independent government according to Dutch customs. The communal government thus ordained was under the leadership of a schout or schultus, who was elected for life by the adult farm owners (gaardmændene) and was under oath only to the representative (Lensmand, later amtsmand) of the king. The schout was chairman of the village council, consisting of himself and seven men called scheppens. Scheppens were elected for one-year terms every New Year’s Day when a village meeting was held. In this meeting it was also customary to read aloud accounts of public affairs and to vote upon village ordinances (vedtaegler), suffrage being the prerogative of the male farm owners. The village had its own law court, also patterned upon Dutch practices. The nine members were the schout, the seven scheppens, and a secretary (shriver). The secretary, also elected by the villagers, was generally the man who became schout when the incumbent died. The court judged in all legal cases except those where the punishment would be “neck or hand,” in which case the king judged. Later, the king’s vassal (Lensmand) came to function as an appellate judge, and in 1576 he appointed two royal chancellors to undertake a revision of the Dutch laws in view of some dissatisfaction that existed with their fairness. Later, still under Christian IV (1588-1648), the Dutch were told to replace their laws with the laws of the Sealand Lawbook and to have the Sealand parliament (Zandslhing) as a superior court. In 1615, on appeal from the Dutch, they were allowed to use the Jutland Lawbook with the royal representative (amismand) in the castle of Copenhagen as a court of appeal, and with ultimate appeal to the king and the royal council. Later yet, “Christia~ V’s Danish Law” was made the law of the nation, but the Dutch were permitted to retain deviating rules in a number of areas, as well as their old form for holding court. Court met four times a year-at New Year’s Day, Easter, Saint John’s Day, and Michael’s Day. As symbol of his judgeship, the schout carried a long white staff and, on opening the court in the name of God, the king, and the congregation, drew three crosses on the table with chalk, to be erased when court was adjourned.

The church in Store Magleby, which had formerly belonged to the cathedral in Copenhagen, was part of the property given the Dutch when they settled on Amager. The first priest was probably one of the original Dutch settlers. Subsequent replacements were speakers of Low German, mostly brought in from the Duchy of Holstein. The parish was independent of the Sealand bishop and exempt from the so-called church tithe and priest tithe, paying only the third of the three divine payments, the king’s tithe. In 1560 the king allocated his tithe to the Sealand see, very likely to reimburse the bishop for the loss of income sustained by the king’s generosity to the colonists. In 1672 the congregation was also exempted from paying the king’s tithe, in return for taking upon themselves all expenses for church, parsonage, priest’s farm, and school. The school may date from the earliest settlement. It was administered by the priest, who was probably also the school teacher. The first mention of a school master is not until around 1640, when it was noted that in addition to a regular annual salary he was entitled to money offerings made by the women at infant baptismal ceremonies. A knowledge of reading, writing, and arithmetic was important in this community where most adult men had an active role in communal administration. The town treasury consisted of a large locked chest in the charge of the schout and, possibly, the secretary. This chest functioned as the village bank. It not only held the village funds but also the fortunes of the inhabitants, including money inherited by minors. Funds came into the public treasury from payments made for the use of communal properties and facilities. Such payments were made by those who grazed cattle on Saltholm or dug its chalk, by the man who leased and ran the Dutch windmill, by any family that had a new grave dug in the cemetery, by the men who fished for eels, and by others. Royal taxes and assessments were levied on the community as a whole, the responsibility for payment falling upon the schout. Since the village chest always contained sufficient funds, it was never necessary to charge local taxes. On the contrary, income from eel fishing alone appears to have been enough to pay the yearly land tax (landgilde) and sometimes there was so much money left over that it was divided among the members of the community. The village was often able to make loans to the inhabitants of the Danish villages of northern Amager against mortgages in land, interest and sometimes land augmenting the wealth of the Dutch community.

The expenses of the community were first of all a money 1and.tax (ZandgiZde) and guest duty (gaesteriafgift), set at 300 marks by Christian I11 and later changed to 100 kurantdaler. In 1547 it was further demanded that the castle secretary (slotsskriveren) in Copenhagen be provided with root crops and onions to meet the needs of the castle and the court; this obligation was probably regarded as a substitute for villeinage labor (koveri), from which the Dutch had been exempted in the privilege letter of 1521. The Dutch were also originally exempt from transportation duty (aegt), but under Christian 111 were required to perform it on the king’s behalf for the royal vassal (Zensmand) in Copenhagen. Set at 24 “pantry-trips” (fadebursrejser) a year, it only amounted to one trip for each farm. In 1541 the right to free and exclusive use of Saltholm was rescinded and the Dutch had to share use and expenses with the Danish Amagerians, the yearly cost being 40 Jochumsdaler (160 marks), plus 200 loads of chalk; the Dutch paid two-fifths and the Danes three-fifths. In the 1660’s these charges were replaced by an assessment according to the amount of land held under cultivation (hartkorn), and gradually they disappeared completely. An extra tax, which soon became a regular annual expense, was 40 rigsdaler a year, to which were added taxes on grain and pork as well as money subscriptions at the time of the Swedish wars at the end of the 17th century. Those earning interest on loans paid the throne 24 percent a year on this income. Finally, there were other smaller communal expenses such as bridge assessments, customs and excise, and payment for eel fishing rights. The village did not pay the priest tithe or church tithe and was exempted from the king’s tithe as well after 1672. For home defense in later years the Dutch were not required to quarter soldiers but did have to provide boatmen for the fleet, 30 or 40 being demanded on some occasions.

THE INDIGENOUS DANISH AMAGERIANS

In the early period of the Dutch colony there were approximately 90 farms in the Danish parish, each leased directly from the king. Generally the right of ownership lasted for the life of the farmer and his wife, although some farms were given to father and son or to mother and son for as long as one of them lived and continued to pay the land tax. On the death of the lessee a new letter of life tenure (livsbrev) had to be obtained; it was most commonly given to a son or son-in-law in return for the promise to pay a renewal charge in addition to the annual rent. The farmers in the Danish villages were subordinate to the king’s vassal in Copenhagen’s castle. The king’s vassal had almost unlimited authority in virtually every aspect of daily life, including farm management, fees and taxes, and villeinage. However, the farmers rarely saw the lensmand, for he was represented in turn by the circuit sheriff (ridefogden), who directly supervised and controlled the area, appeared in court in law cases such as tax or lease disputes, and on the whole represented the king’s vassal and the king. In each village, subservient to the circuit sheriff, was a local sheriff (foged) or alderman (oldermand), generally one of the biggest farmers in the area. It appears that the alderman was elected for life by the villagers, subject to the sanction of the king’s vassal. It was his job to see to it that the town ordinances were kept, that the farmers worked without complaint or disturbance, and that problems which occurred were, if possible, resolved without resorting to lengthy and expensive court proceedings. The alderman also assigned farmers their turns in transportation duty, road work, and work on other public projects, on the whole carrying out the will of the crown and the royal vassal. In return he was freed from certain extra taxes, transportation duty, and public work.

When the Dutch came, the old Amager judicial district (birk) was divided; the Dutch became independent and the Danes came under a new jurisdiction, the Taarnby district court (birketing), functioning under the royal vassal and headed by a court sheriff (tingfoged). The latter, at first one of the district’s most important farmers, was later called district sheriff (birkefoged), and instead of a farmer became a city man trained in law and governmental administration. The position required ability to read and write, which was uncommon at that time, as well as familiarity with the old laws, legal rules and orders of the king and the council of the kingdom (rigets råd). He was assisted by the court secretary (tingskriveren), also trained in law. Both district sheriff and court secretary had to sign all judgments, decisions, and ordinances. The court met on Fridays in the Amager village of Taarnby (Tårnby) and consisted of twelve jurors (tingmænd or stokkemænd) in addition to the district sheriff, sitting as judge (birkedommer), and the secretary. To be a juror was a royal duty divided among the older villagers; there were generally two from each village. The court had jurisdiction even in cases concerning “honor and life,” but the authority of the judge became more and more absolute until the jurors had no influence in decisions. The farmers responded by neglecting their duty so that non land-holding farm laborers (husmænd) came to be taken as permanent jurors in return for having their houses freed of taxes and royal burdens. Around 1700 the number of jurors was reduced to nine. The original court sheriffs were paid partly from the fines collected and partly in exemption from the land tax and most of the other burdens common to tenant farmers. In 1578 it was ordered that each farm in the district was to give a certain amount of “judge-grain” to the sheriff, but this was soon replaced with a money assessment amounting to two marks from each farm; although many were in arrears in their payments, the total sum due the judge in the 17th century was around 100 Sletdaler, a rather good wage for that time. The court secretary was paid out of the money collected in fines. Judgments could be appealed to Sealand’s (Sjælland) parliament (landsting) as a superior court when it was a matter of life, honor, or property. Such cases were common, since the court was strict and the offenses included fornication and adultery, fighting, “neglecting the court,” holding a big wedding, and illegal sale of liquor. Many of the cases concerned extramarital sexual affairs, which were severely punished. According to a law of 1558, adultery was punished the first time with loss of nonreal property and money to the last farthing, the second time with loss of all property including real estate, and the third time with decapitation for the man and drowning for the woman. A man guilty of defloration of a virgin had to pay nine marks to the woman’s guardian plus eight Skilling grot to the court. On Amager as a whole, one or two cases of sexual misconduct (lejermaalssager) were generally tried each year. Most of the offenders were Dutchmen, who had been made subject to similar proscriptions on sexual conduct during the reign of Christian IV (1588-1648).

Taarnby church, like that of Store Magleby, had been an annex of the cathedral in Copenhagen. In 1474, before the Dutch colonization, the two Amagerian churches and the cathedral were taken from the pope and put under the jurisdiction of the university; the income from the churches was to provide wages for university teachers, who in turn were to hold church services or have them performed by a vicar. Apparently the crown had a superior right, since the churches were given in fief to the secretary of the castle (slotsskriver) in Copenhagen. Oftentimes the king obtained money by selling rights to church income and priest tithe, and the buyer then had the responsibility of providing a curate for the church. Following this custom, Taarnby church came under the jurisdiction of the university again in 1542, remaining there during the following centuries. The university had the right to appoint the priest for Taarnby parish, which had economic importance for the university faculty in providing a place of retirement for old professors. The congregation seldom had a word in the choice of their pastor, in spite of the church ordinance of 1539 which made free choice a legal right. Indeed, they usually did not even have a chance to hear him preach before he was called to his post.

Without a school before the 1700’s, only a few of the farmers obtained any education for their children other than the teaching of the catechism by the priest after Sunday church services.

The Danish Amagerians were not land-bound serfs. On the contrary, in order to retain their farms they were subject to various taxes and assessments. The land tax was originally eight barrels of barley for each farm, but was later increased by two barrels of oats. Guesting expenses were levied on the villages as wholes, and amounted to approximately one-fourth of a cow, one sheep or pig, or two lambs, one goose, four hens, and one daler in money from each farm every year. It is not known when these payments were changed to money, but the old rules were still in force around 1700. The tithe, not literally a tenth of the farmer’s crops, was divided into three parts-king’s tithe, church tithe, and priest tithe-and the amount of each was determined independently, varying yearly according to the harvest. The king often leased rights to his tithe, and thus in 1560 he gave the Taarnby king’s tithe to the bishop of Sealand, probably as a replacement of the loss sustained by the bishopric when the church was given to the university. At first the amount of villeinage which could be required was unlimited, and the Danish men were sometimes required to work daily during sowing, harvesting, and plowing seasons to the detriment of their own farm livelihood. In response to a complaint in 1529, the king set a maximum to the amount of work that could be demanded; the farmer had the right to be released from more than the maximum amount in return for paying one-half Lødemark. In 1624 complete freedom from villeinage could be purchased for 300 Speciedaler a year for the parish (four Rigsdaler per farm), which was more than the Dutch paid in land tax for their whole parish. Exemption from villeinage did not include freedom from transportation duty, which, however, did not become oppressive until after the inauguration of the absolute monarchy in 1660. In 1627, for example, each of 80 Danish farmers was required to bring two loads of firewood to the court in Copenhagen. In addition to these permanent annual taxes, assessments were made which themselves often became permanent. During the long war with Sweden in the 1560’s the government added special assessments in money and provisions and required the inhabitants to quarter soldiers. The extra tax or land help (landehjælp) of one Daler from each farmer soon became a regular yearly expense, and under Christian IV it was doubled and tripled, with the addition of a grain tax, a pork tax and, in 1646, a copper and tin tax. During armament for the Swedish war of 1658-60 there were a number of new taxes such as a cattle tax of one mark a head and a monthly contribution in money, a defense tax of twenty Speciedaler from each farm, an increase in land help, pork tax, and grain tax. Finally, under Christian V, these taxes were unified by assesing a single tax according to the amount of land under cultivation (hartkorns-kontribution).

RESUME OF THE EARLY DIFFERENCES

With the settlement of the Dutch in the southern part of Amager, the island became the habitat of two distinct societies, each with its own culture. In their own eyes and in the eyes of their contemporaries, the socio-cultural differences were of considerable magnitude and importance. The Dutch farms were privately owned and could be sold or inherited, subject only to the payment of taxes and assessments. The Danish farmers were the king’s tenants, with only life-time leases. The Dutch community was governed by locally elected representatives according to Dutch procedural form and law (later, Danish law codes with allowances for Dutch practices). The Danes were governed by outsiders according to Danish law codes, their locally elected representatives acting only to enforce decisions made outside of the community. The Dutch lived under pronounced, voluntary communalism, while the Danes functioned as individuals except when forced by the government to act as a body. The Dutch owned their own church, chose their own Low German-speaking priest, and followed Dutch Protestant ritual. The Danes worshipped in a church belonging to the University of Copenhagen under a priest chosen independently of their wishes, according to Danish Protestant ritual. The Dutch supported their own church and minister. The price paid for religion by the Danes went to powers outside of the community. The Dutch had public schools. The Danes waited approximately two centuries before their children could get an elementary education. The Dutch, like the Danes, were subject to land tax, guesting duty, transportation duty, and special assessments, but the land tax was levied on the village as a whole and continued to be based upon a community of twenty-four farms. In addition, they were free of villeinage, which greatly oppressed the Danes. Dutch economy differed from Danish in its emphasis upon dairying, horse breeding, eel fishing, and vegetable cultivation as opposed to grain farming. All of these differences were epitomized in the view of contemporaries by the possession of mutually unintelligible languages, different types of clothing, differences in houses and furnishings, and different customs in the celebration of holidays and personal events such as engagements and weddings.

Social intercourse was limited almost entirely to meetings resulting from spatial propinquity, the major exception being those instances in which Danish farmers mortgaged their farms to the Dutch. Socializing was kept to a minimum, and each sought out their own. The Dutch did not permit intermarriage; no Dane could be brought into Store Magleby and any Dutchman who married out was no longer considered a member of the community and was not allowed to participate in village affairs nor enjoy their special rights and privileges. This practice loosened somewhat later on.

ETHNIC ACCULTURATION: THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

For the first two centuries the Dutch increased in wealth and numbers. The original 24 families which established the colony in 1520 had become approximately 75 families in 1600, 80 in 1615, and 130 in 1650. In 1651 twenty families moved to the island of Sealand on the other side of Copenhagen to found the colony of New Amager. The plague of 1654 and the contemporaneous Swedish war reduced the population temporarily. Thirty farms and houses were abandoned, most of the farms supporting two or more families. By 1688, however, the population had increased again to 99 families in Store Magleby and 30 in New Amager (other parishes).

The Danes, depressed to begin with, sank lower and lower into poverty under tax burdens, assessments, and villeinage. Soon after arriving the Dutch took over the two farms in Dragør, “the king’s fishing camp” south of Store Magleby. In 1547, and again in 1574, royal permission was obtained to lease farms in the Danish villages, and the subsequent infiltration of the Dutch into the Danish parish increased at an accelerated pace. By the time of the wars which preceded the absolute monarchy in 1660, one-fourth of the Danish land was in Dutch hands. During the early decades of the absolute monarchy the economic position of the Danes deteriorated rapidly; by 1680 the Amager Dutch averaged 3.5 horses or cattle to every 1.363 hectares of land, while the Amager Danes averaged only 1.5. During this recession many Danes were forced off their farms into the land laborer or worker class, and the farms were invariably taken over by the Dutch. In the prewar period many cases occurred in which the Dutch loaned money to the Danes, and the creditors received ownership or usufruct of the land. After the war, in order to get the national economy on its feet as rapidly as possible, the king overlooked the fact that such farms were taken over without lease or payment to the crown, thus bringing life leases to a de facto end at the same time that a fifty-year period was inaugurated during which the land tax was not demanded. By the time the land tax was required again in 1708, much of the Danish farm land was in the hands of the Dutch.

The Dutch farmers came into positions of influence and power in the Danish towns. In 1672 the sheriffs of Tømmerup and Ullerup were Dutchmen, and by 1691 Dutch officials were also to be found in Maglebylille and Sundyvester. By 1718 almost one-third of the farmers in the Danish towns were Dutchmen who had taken over Danish farms either completely or in part as creditors, or had leased the farms from the crown. All of the large farms, in particular, were in Dutch hands.

Some of the Dutch worked the Danish lands as part of their own farms, while others moved to the new farms. All, however, continued to regard themselves as belonging to the mother village and for the most part managed to avail themselves of its privileges, especially with respect to permanent ownership of property and freedom from villeinage. In cases where Dutch were elected officials of Danish villages, it was because of their influence with the authorities deriving from their wealth and reputation for dependability and punctuality, and not because they had amalgamated with the Danes. In social life they kept as much as possible to the Dutch community, speaking Dutch and avoiding the Danes in daily life, regarding the latter as economically, socially, and intellectually inferior. Endogamy was a strict rule, and in the 17th century the king’s permission was frequently sought to marry within the third degree of kinship; permission was always given in return for a judgment in favor of the poor, generally a hospital, although sometimes the king appropriated one-half of the sum for himself. Nor would the Dutch permit their children to work for Danes, not even, it was held, if it were for the most important man in the kingdom. In addition to guarding their social and cultural integrity, the Dutch retained their special reIationship to the royal house, the basis for their prosperity, by always being prompt in payments due the crown and by continuing to supply the capital and the court with their desirable products. Unique in their way of life and protected by the royal house, they stoutly insisted that they were not peasants (bønder) but “the king’s Amagerians.”

In contrast to their conservative neighbors, the Danes changed and came more and more to follow the Dutch way of life. In particular, they adopted the Dutch economy, learning to cultivate vegetables and to emphasize dairying, horse breeding, and eel and herring fishing. Every Wednesday and Saturday all Amagerians carted their produce to the market at Amager Square in Copenhagen. Before the coming of the Dutch mostly fish was sold, but the Dutch created a reputation for fine vegetables, cheese, and butter-milk, and became especially known for their sweet cup-butter (“søde koppesmør”) which was sold to “gentlemen and bishops.” The market constituted the most important source of money income for Amagerians, and the Danes began to capitalize on the success of the Dutch by offering similar products for sale. In order to do this, it was found advantageous to present themselves as Dutchmen, and by the 17th century it was customary for them to wear a variant of the Dutch national dress. Although not able to obtain the special prerogatives of communal government, land tenure, and villeinage exemption held by the Dutch, they did adopt at least one legal custom; in 1686 royal permission was received to use the Dutch rules of inheritance which divided property equally between sons and daughters, rather than the Danish rules which gave twice as much to a son as to a daughter. By the last half of the 17th century the Danes were clearly borrowing traditions out of a pure desire to be Dutch undiluted by obvious economic motivation; for example, they adopted the Shrove Tuesday (fastelavn) celebration of the immigrants, even though they were not able to match the rich display of the latter. Finally, there was an important but poorly documented diffusion of the Dutch propensity for steadfast hard work, initiative, and reliability.

Relations between Dane and Dutchman were not entirely free of conflict. As already noted, the indigenous farmers objected to expulsion from the island by Christian II in 1520 and succeeded in retaining or regaining much of their original territory, primarily under the protection of King Frederik I. In subsequent decades the outstanding trouble spot was Dragør, the royal Danish fishing village on the southern, Dutch part of the island. In 1520 the village, with two farms and a small fishing population, was no longer the important center it had been in the late middle ages when the Hansa league flourished in the Baltic. But during the 16th and 17th centuries its population grew steadily. On the one hand, Dutchmen came. The two farms of the village were leased by the king to Dutch farmers. In addition, the Store Magleby village government financed expansion and improvement of the harbor, thereby gaining rights to participation in shipping, fishing, and ship-salvage; this resulted in the influx of many young Dutchmen, especially from families with more sons than the paternal farm could support. On the other hand, Danes immigrated from Sealand and the larger Sound area, coming to fish, salvage, and participate in the small-scale shipping of produce, firewood, and building materials.

The Dutch acquired political control of Dragør. Around 1600, when Hansa trade no longer necessitated a customs agent in the village, the job was given by the king to the schout (Byfoged) of inland Store Magleby, who thus came to function as the supreme local authority (foged) in both villages. When Dragør later became larger, the schout got royal permission to appoint a deputy sheriff (underfoged) as resident chief of the harbor village, and a fellow Dutchman was always chosen.

While the Dutch Dragorians profited from this arrangement, the Danish did not. The latter were forced to share the obligations of the residents of Store Magleby, such as contributing to the payment of the Dutch land tax, without receiving the corresponding privileges; for example, they had no part in the commons, not even enough to tether a goose. In the long-continued dispute, sole recourse was to the king. Standing before the throne in 1674, the Dutch pleaded that the two communities, always united in the past, should continue to form parts of a single church parish and politico-legal district. In spite of its basis in an incorrect statement of local history, the plea was upheld. Although there is no record of violence, Dragorian Danes continued to complain during succeeding decades, but as long as the Dutch enjoyed the special benevolence of the king, complaints were in vain and grumbling was the only solace.

FOLK AMALGAMATION: THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES

Between 1700 and 1720 Denmark was at war with Sweden, and as in previous Dano-Swedish wars, Amager suffered greatly; it was overrun and destroyed by armies, and drained of all resources to supply the besieged capital. The disaster of the prolonged war increased when the Black Plague struck in 1711, leaving half of the island’s inhabitants dead and as many as two-thirds in two of the Danish villages. This time the Dutch did not have the resiliency they had displayed in responding to past disasters, no doubt because of the royal act of 1717 which ended their special privilege of a permanent land tax assessed on Store Magleby on the basis of the original twenty-four farms. A number of the farms in both the Danish and the Dutch parish were left uninhabited in 1711, and even after 1750 there was still frequent mention of abandoned farms (ødegårde).

The Dutch no longer enjoyed superior economic position; they had lost special privileges. And developments following the introduction of the absolute monarchy had resulted in a de facto end to life-time limits on farm ownership in the Danish parish; Danish property ownership now also included the right to sell and inherit with freedom from taxation on property transfer. In addition, the Danes had adopted the profitable farm economy of their neighbors.

The Dutch who suffered these changes in the second decade of the 18th century were reluctant to give up their socio-cultural integrity, but they were now fighting a losing battle against many of their own younger generation as well as against the Danes, who had ceased to be socioeconomic inferiors. In 1731 a Danish priest was called to work at Store Magleby church beside the Dutch priest, so that church services could now be offered in both languages, and in 1735 the first Danish language wedding ceremony was held. The biggest break in the ethnic barrier came in 1758 when the schout of Store Magleby married the daughter of a well-known and respected Dane, the sheriff (foged) of the Danish town of Sundbyvester. The first sanctioned marriage of a Dutchman to a Dane, it was followed the next year by the marriage of the secretary of Store Magleby to another Danish girl from Sundbyvester. Before long, Dutch and Dutch-mixed elements dominated the whole island. In the 1770’s half of farms in the Danish parish were in Dutch hands and only five farmers were not in an “in-law” relationship with the Dutch.

In 18th century Dutch homes, people still spoke their own language, which by then was a mixture of Dutch, Low German, and Danish. For some time the men had been able to speak Danish; from the first they had known enough to deal in the Copenhagen market place and from an early period they had been forced to use Danish in law cases which came before the king or his vassal, as well as in other communications with the court. Yet, in law cases of a purely local nature, Dutch was used. The communal laws of 1711 were written in Dutch, and school and church functions were conducted in Dutch. In 1788 the Dutch priest issued a school-book in Low German, and the Dutch song book, authorized in 1715, was still in use around 1800. By then, however, many people in the community spoke only Danish. When new communal laws were drawn up in 1811 they were written in Danish, and in the same year Dutch ceased to be used in church services. In 1818 the special jurisdiction of the Store Magleby court was revoked and the Dutch came under the Danish court system.

Some adults of the mid-19th century attempted to perpetuate the Dutch language. A traveler in 1846 described a family in which the old farmer wrote a Dutch glossary for his son’s Danish wife. But it was a hopeless fight against the younger generation, which could see no advantage to speaking Dutch rather than Danish.

With intermarriage, loss of language, and loss of unique forms of communal organization, the Dutch merged with their Danish neighbors. The result was neither a Dutch nor a Danish culture, but an Amager culture-strongly Danish, but differing from the rest of Denmark in a number of ways. Above all, Amagerians had their own form of economy, adapted to the contemporary market by increasing specialization in vegetables and the development of flower cultivation (especially tulips and carnations) at the expense of fishing and dairying. They had their own dress which, though changed considerably from its prototype in Holland, still distinguished the King’s Amagerians from other Danes. The Scandian dialect of Danish spoken on the island had acquired words and sounds from Dutch, including a certain singing tone in the vocals. Details of housing and furnishing, such as the so-called Amager shelf, were distinctive features, as were holiday activities such as rolling and throwing eggs at Easter time, eating “bag porridge” at Christmas, and ceremonially riding the rounds of the farms on horseback at Shrovetide (Shrove Tuesday). Amagerians were known for their fine products, for their propensity for industriousness, and for reliability. Amager culture of the 19th century, an amalgam of Dutch and Danish proudly shared by all regardless of ethnic background, was unique enough to set the islanders off in contemporary eyes as the “Amager Dutch,” purveyors of the best cabbages and vegetables in the realm.

URBAN ASSIMILATION: THE 20TH CENTURY

The means of communication with Copenhagen changed radically in the 1900’s. For centuries roads were maintained by the farmers themselves; the inhabitants of each town formed corvCes (?), and their work was supervised by local aldermen and subject to inspection by the king’s vassal and his circuit sheriff. Under this arrangement roads were narrow, the surfaces deeply rutted in summer and winter and muddy bogs in spring and fall. The situation was not improved in 1790, when toll was charged. Half of the money collected went to Amager residents and the other half to the state for road maintenance, but half of the toll was not sufficient for repairs. This resulted in vociferous complaints in the 1830’s and a change in organization in 1840, when road care became the responsibility of a state agency. During the rest of the 19th century the roads were improved, and in the 20th century the main roads were given an asphalt surface.

When the Dutch first came to the island it was connected with the capital only by a ferry. In the first half of the 17th century a small foot-bridge was built which Amagerians used in the transportation of goods in hand-carts, and around 1660 this bridge was expanded and strengthened to accommodate horse drawn wagons. In 1686 a second bridge was built, although most Amagerians continued for a long time to use the older one. These bridges, since rebuilt several times, are still the only dry connections with Sealand and the outside world.

Around 1600 Christian IV erected a gate on the island through which all travelers to the capital had to pass, and from that period until about 1850 it was the means by which all traffic was controlled; it levied a toll on market goods and denied passage during the night hours. Over poor roads and through this gate, centuries of Amagerians drove wagons to market on Wednesdays and Saturdays, but otherwise seldom ventured from their island. Even on these twice-weekly trips, however, they rarely had cause to go beyond the market place (Amagertorv), and intercourse with Copenhageners was limited to commercial dealings. Urban influence on Amagerian culture was minimal.

Both the city and the means of communication changed. The population of Copenhagen, which was ca. 10,000 in 1500, grew to be 102,000 in 1801,477,000 in 1901, and about one million in 1951. In the 1890’s bicycles came into use as a means of communication which all could afford. In 1907 a railroad was built along the isIand to offer regular, although somewhat expensive, transportation to the capital. The growing city began to expand across the bridges and onto the northern part of the island, where some farms gave way to suburban residences, and small summer villas were built along the beaches. However, most Amagerians were little affected. Their daily life continued much as before, and the most notable change was the disappearance of the Amager costume. In the 1880’s the last man died who wore this distinctive garb; women ceased to wear it after the turn of the century except on holidays and to family celebrations, and since 1940 it has become rare even on these occasions. In part this was the result of pride attaching to the wearing of city clothes, but it was also argued by those adopting the new styles that the old were prohibitively expensive and very uncomforable.

…

Over the last six centuries, Denmark has experienced continuous immigration of groups and individuals into the country, including Dutch farmers in the early 16th century, and Jews from several European countries in the 17th century. The Dutchmen were invited by King Christian II in 1521, and the Jews arrived at the express invitation of King Christian IV, who thought they would vitalize the commercial life of Denmark.

The constant inflow of Germans between the mid-17th and the mid-19th century left a particularly deep impact on the development of modern Denmark, culturally as well as economically.

During the second half of the 19th century and until World War I, sizeable numbers of unskilled workers arrived from Poland, Germany, and Sweden, sometimes expressly invited by the government or attracted by religious privileges.

There are no precise estimates of immigrant numbers for these early periods, but there is little doubt that they were considerable. In 1885, for example, foreign citizens constituted eight percent of the Copenhagen population. Germans came in great numbers to harvest potatoes. And, in 1914, 14,000 Polish citizens arrived on the islands of Lolland and Falster to do agricultural work in the turnip fields.

In the course of a few generations, all these groups were gradually assimilated into everyday Danish life and culture, even though their special backgrounds in certain cases are still identifiable, for instance in the form of religious communities.

Immigration during the 20th century primarily consisted of multiple waves of refugees. The two World Wars brought many east Europeans, Jews, and Germans to Denmark. In the 1970s, Denmark accepted refugees from Chile and Vietnam, probably some 1,000 annually. The Cold War, the breakdown of empires and federations, and conflicts in the Middle East led to the arrival of several new groups through the 1990s, particularly Russians, Hungarians, Bosnians, Iranians, Iraqis, and Lebanese.

None of these groups came in large numbers (for instance, about 1,400 Hungarian refugees were accepted in 1956), but, on aggregate, they and their descendants began to represent sizeable numbers by the 1980s and 1990s.

Until the mid-1990s, in fact, refugees were generally welcome in Denmark, particularly those from former communist regimes. As more refugees began to arrive from third-world countries, however, a shift of policy and perception started to set in. Repatriation became an integral part of temporary residence programs from the early 1990s. Since 2001, refugees have clearly been discouraged from applying for asylum, and numbers have declined dramatically.

For a short spell between the late 1960s and 1973, Danish companies imported so-called guest workers, especially from Turkey, Pakistan, Yugoslavia, and Morocco. Exact numbers are not available, but by the time the stop to labor immigration was introduced in 1973, residents from these four countries numbered some 15,000.

When Denmark entered the European Community (now European Union) in 1973, it became possible for citizens from the other Member States to settle and work in Denmark and obtain access to social rights. The same opportunities had already been open to Nordic citizens since 1952, when Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark signed a passport union allowing for the free movement of people across Scandinavian borders.

More about the Dutch (See * below)

In 1521 King Christian II invited 184 Dutchmen to Denmark, and promised them ownership of the Island of Amager (with the exception of the City of Dragør) plus the island of Saltholm, if they would undertake to provide the necessary food to the court at Copenhagen Castle. A letter of priviledge was issued in haste, freeing the Dutchmen of taxes, and granting them free hunting and fishing rights among other priviledges, in return for the steady delivery of fish, onions, carrots etc. to the Danish court, plus a small annual fee to the king. Denmark was in need for immigration of skilled labor. They arrived in the country with both wives and children, and they probably counted about 700-800 people in total.

Precisely when the Dutch arrived is not known exactly, as the paperwork was destroyed in the wars against the Swedes, most likely the “Torstenson war” in 1643-45, which left Denmark as the losing part. Laird and historian Arild Huitfeldt (1546 – 1609) wrote in his Danish Constitution Chronicle among others the following about immigration: “In 1515 the king negotiated in Vaterlandene in Netherlands that hither should be received some Dutchmen to stay, which he promised in great freedom, and in the spring of 1516 some arrived here, which he gave a town on Amager to stay at, called Dutchman city, which the Queen [More accurately her Mother, Sigbrit] very much helped because this People especially knows how to make Butter, Cheese, Roots, Bulbs, etc. which was a Benefit of Copenhagen City “. (Frely translated)

The Dutchmen sustained a small gated community with its own language, its own laws and their own customs. A Schout was appointed, and it was a highly trusted job. He was at the same time chief of police, sheriff, judge, auctioneer and chairman of the municipal council. As a peculiarity, Church books in the Dutch town testify that mixed marriages until the mid-1800s was a rare exception, which tells us that it was a fairly closed society for quite a long duration of time.

When Christian II a few years later lost power in the country, the Dutch also lost rights. They had to settle with the southern part of the island of Amager, and so they settled in Store Magleby, which inherently changed its name to “the Dutch city” (Hollænderbyen). The Danish peasants in the area were permanently moved out, probably to a small fishing village called Hundested.

The Dutchmen lived as free independent farmers in a closed fraternity, socially and financially independent, and they were, as it was written in 1758, “…absolutely not devoted to drunkenness, fights or the like”. The same could not be said about Danes. Accordingly a priest from one of the villages in Zeeland (Sealand, Sjælland) wrote: “What the farmer are most receptive to learning in the capital city, is drunkenness, he also inhale his defiance, all kinds of fraud and impurity of the heart, and the women in the capital city have no less than a harmful influence on him.”

The Dutch were in short, an industrious people, who not only did good business at Amagertorv on the city’s official market days on Wednesdays and Saturdays, but also held additional sales on Sundays in the middle of church time. They saved up and gradually came to constitute the social upper class on the island. Their vegetables were of the best quality, but dairy products were more difficult. The milk was thin and the cheese was acidic, but there was a probable explanation to this, as the cows were fed with cabbage leaves, thus making proper cheese difficult.

For nearly 300 years, the language of this part of Amager a mixture of Low German and Dutch, which may have caused a few problems with the neighbors. In Tårnby (another major city of the island of Amager) the peasants spoke Danish, and in Dragør the indigenous people’s own language sounded like a mixture from Skåne and Bornholm. But they dealt with the linguistic confusion on a daily basis.

People in the villages looked after themselves. But on Sunday, there were skirmishes, for until 1885 Dragør didn’t have it’s own church. Parish priest in the Dutch town who spoke Low German, was also soul shepherd for the Danish citizens of Dragør, and through a couple of hundred years, it is hardly credible that they have understood many words from the pulpit. The relationship between neighboring towns were tense between the two hostile cultures, and it didn’t make things better that the Danes from Dragør had to pay for religious ceremonies like baptisms, weddings and funerals, and finally had to pay rent for the burial at the cemetery, while the inhabitants of the Dutch city of course would not pay to be buried in the soil, the King had owned for centuries.

Today

A number of Dutch names are still common on Amager: Bacher, Dircksen, Isbrandtsen, Jans, Palm, Zibrandtsen etc., and 12 streets close to where I live, bear Dutch male names: Adriansvej, Backersvej, Dirchsvej, Gerbrandsvej, Gertsvej, Greisvej, Jansvej, Peitersvej, Theisvej, Tønnesvej, Wibrandtsvej and Willumsvej. Likewise, many descendants of the Dutch still use Dutch given names in their families: Adrian, Dirch, Grith, etc.

* Forskerteam vender op og ned på historien om kong Christian II’s indkaldte ‘hollændere’.

Dirch Jansen Schmidt bor på Fælledgården i St. Magleby på Amager. Han er gartner og dyrker grøntsager – ligesom sit ophav, den hollandske bonde Sigbrandtsen, der sammen med godt 160 andre hollandske landmænd blev hentet til Amager i 1521 af kong Christian II.

Familiens arv

Sådan lyder den næsten 500 år gamle fortælling, som Dirch Jansen Schmidts 59-årige liv har været præget af. Dirch Jansen Schmidt er vokset op med amagerdragter, og han ejer selv en, som oprindeligt blev syet, da hans oldefar i 1886 skulle giftes. Dirch Jansen Schmidt er opdraget med stærke, lokale traditioner som tøndeslagning, og hans tre børn har alle fået et hollandsk navn. Neel, Marchen og Grith hedder de – i respekt for familiens arv.

I det stadig bevarede privilegiebrev om det modelsamfund, Christian II ville opbygge på Amager, omtales indvandrerne som hollændere. Det bed sig fast. St. Magleby hedder også Hollænderbyen. Her ligger Hollændervej og Hollænderhallen, og på resten af Amager finder man f. eks. Willumsvej, Dirchsvej og Gertsvej. Hele vejen op gennem danmarkshistorien omtaler historikerne indvandrerne som ’hollandske bønder’ fra ’egnen nord for Amsterdam’.

Ny opdagelse

Men meget tyder på, at det verdensbillede er forkert.

Arkivar Lis Thavlov er overbevist om, at Christian II, der ønskede friske grøntsager på middagsbordet, i virkeligheden hentede ’Kongens bønder’ i det, der i dag er Belgien.

»Der var på det tidspunkt ingen grøntsagsdyrkning eller mejeribrug i Waterland i det nordlige Holland, hvor man hidtil har regnet med, at indvandrerne kom fra. Flytter vi blikket til Flandern lidt længere sydpå, finder vi både et landbrug præget af grøntsagsdyrkning og det købstadsstyre, som Christian II også var interesseret i at indføre«, siger Lis Thavlov, der i dag leder Silkeborg Arkiv.

Også for hende er det en ny erkendelse. I 1996 var hun ansat i Dragør Lokalarkiv, der også dækker St. Magleby. Dengang skrev hun i anledning af 475-året for indvandringen en artikel om ’Den hollandske indvandring til Amager i 1500-tallet’, hvor hun også omtaler ’gruppen af indkaldte hollændere’.

Men nogle år senere kom hun i kontakt med Willy van Hoof, en belgisk amatørhistoriker med speciale i gartneriets og landbrugets udvikling gennem tiderne. Han mente ikke, den traditionelle danske opfattelse kunne passe, og de to har nu i fællesskab givet hollænderteorien et kritisk gennemsyn i bogen ’Vlaamse Tuinders en hollandse boeren in Denemarken in de zestiende eeuw’ (Flamske gartnere og hollandske bønder i Danmark i det 16. århundrede. Et kritisk blik på en velkendt indvandrerhistorie), der udkom i marts og endnu ikke er oversat til dansk.

De to er overbeviste om, at i hvert fald de fleste af ’Kongens bønder’ blev hentet i Flandern i den sydlige del af Nederlandene og blev udskibet i Nieuwpoort.

For Dirch Jansen Schmidt, hvis Fælledgården er bygget af hans oldefar Crilles i 1888, er det helt nye oplysninger:

»Vi bliver nødt til at se på historien så korrekt som muligt«.

Gode forretningsforbindelser

Men lad os først kaste et blik tilbage til dengang, den danske konge udså sig Amager til at opbygge et lille modelsamfund ved hjælp af indvandrere fra den mere moderne del af Europa.

På Christian II’s tid – han var konge 1513-23 – var Danmark en europæisk stormagt. Danmark, Norge og Sverige var via Kalmarunionen ét rige, og Danmark strakte sig dengang næsten ned til Hamburg.

Christian II var en energisk hersker, og på programmet havde han bl.a. en modernisering af riget. Forbilledet var Nederlandene, der omfattede det meste af det nuværende Belgien og Holland. Han kendte området godt. Både hans hustru, dronning Elisabeth, hans elskerinde, Dyveke, og rådgiver, Mor Sigbrit, kom derfra.

Margrethe af Østrig var for den tysk-romerske kejser Karl V statholder i Nederlandene, og hun havde opdraget Karls søster, den senere danske dronning Elisabeth, på sit slot i Mechelen i netop den del af Nederlandene, Flandern, hvor grøntsagsdyrkningen gjorde store fremskridt.

Chritian II’s forretningsforbindelse i Nederlandene var købmanden Pompejus Occo, der bestyrede det hovedrige tyske finans- og handelshus Fuggers filial, et såkaldt faktori, i Amsterdam.

Fugger drev kobberminer i det nuværende Slovakiet og udskibede datidens vigtigste metal i Østersøen. Skibsladningerne skulle gennem Øresund, hvor danske konger opkrævede told.

Fuggerne ville gerne stå sig godt med det danske kongehus. Så Pompejus Occo var hjælpsom. Han lagde ud, når Christian II købte våben og andet udstyr, han var vært under kongens besøg i Nederlandene og organiserede de specialister, den danske konge ønskede. Et af de få bevarede dokumenter i hele sagen er faktisk en regnskabsbog, hvor der står, at Occo får betaling for fem skibes rejse fra Nederlandene til Danmark i 1521.

Amager som mønstersamfund

I forbindelse med planen om et mønstersamfund på Amager skal man også notere, at Christian II var på en længere rejse i netop Flandern samme år for at studere den tids mest moderne samfund.

Bortset fra privilegiebrevet og regnskabsbogen fra Pompejus Occo findes der i dag ingen dokumenter om selve rekrutteringen i Nederlandene eller arrangementet i det hele taget. Det meste er gået tabt under krige, ved brande eller bare forsvundet – både i Nederlandene – nu Holland og Belgien – og i Danmark.

Christian II tog sit arkiv med sig, da han flygtede. Det var længe forsvundet, men blev fundet i Tyskland og har siden 1939 ligget i Rigsarkivet som ’Münchenarkivet’.

»Vi har desværre ikke haft held til at finde det endelige bevis i form af dokumenter«, indrømmer Lis Thavlov. »Til gengæld er indicierne stærke«.

Men netop når det drejer sig om dokumenter, synes hun ikke, man skal overse den belgiske arkivar Emile Vanden Bussche, der på basis af originale kilder i Nieuwpoort i 1879 og 1881 skrev, at der var flamlændere blandt indvandrerne til Amager. Det er ikke lykkedes van Hoof at genfinde dem.

»Vi har ikke papirerne, der bl.a. omfatter en arvesag, men der er ingen grund til at tro, at Vanden Bussche ikke skulle have set dem og citerer dem korrekt. Så de kom altså fra Flandern«, siger Lis Thavlov.

»Vi har også ledt efter dokumenter i hollandske arkiver, men ikke fundet et eneste spor af, at indvandrerne til Amager skulle komme derfra«.

Sprogforvirring

Nok så afgørende er det ifølge Lis Thavlov, at der i Waterland i begyndelsen af 1500-tallet slet ikke blev drevet havebrug og gartneri, men på grund af havets hyppige oversvømmelser et meget ekstensivt landbrug med vægt på kvægavl.

»Christian II ville importere noget moderne – altså gartnere og frugtavlere. Vi må også tage i betragtning, at dronningen fra sin barndom i Mechelen var vant til at spise grøntsager. Det giver ingen mening at hente indvandrere fra området omkring byen Hoorn – også kendt som Waterland. Det ville være, hvad vi i dag kalder økonomiske flygtninge. De havde slet ikke den ekspertise, Christian II ønskede«, påpeger Thavlov.

»Ser man på indvandrernes sprog, navne og medbragte traditioner, fortæller de først og fremmest om Nederlandene. Alle nederlændinge talte samme sprog, og for eksempel tøndeslagning fra hest, der stadig er tradition på Amager, kender vi fra alle egne i Nederlandene. Den særlige amagerdragt, som de stadig bruger, er heller ikke speciel for det nordlige Holland«, siger hun videre.

»Endelig er der jo sprogforbistringen. I Danmark taler man som regel om Holland, selv om landet hedder Nederland – Holland er kun to små regioner i den nordlige del af landet. Jeg er tilbøjelig til at tro, at forvirringen ikke er af ny dato. ’Holland’ var ikke en præcis stedsangivelse, men snarere et udtryk, der dækkede hele området. Ligesom Waterland faktisk også er en flertydig stedbetegnelse«.

Forfriskende, men kun indicier

På Amagermuseet i St. Magleby synes leder, ph.d. Ingeborg Philipsen, det er en interessant teori, som hun ikke vil afvise:

»Vi har allerede i udstillingen blødt den traditionelle opfattelse af indvandring fra Holland op og henviser både til Nederlandene og til Holland. Vi ved, der står Holland i privilegiebrevet, men det kan jo være en fejl – at der i virkeligheden skulle stå Nederlandene. På det her område var og er der en sprogforvirring«, siger Ingeborg Philipsen.

Hun lover i samme åndedrag, at museets hjemmeside opdateres om kort tid, så tvivlen om oprindelsesland eller rettere oprindelsesegn også kommer til at fremgå her.

»Men så vil jeg også sige, at vi jo her kun har en hypotese bygget på indicier – ikke et dokumenteret forskningsresultat«, tilføjer hun.

Historikeren Aske Laursen Brock, der har beskæftiget sig med Christian II’s indvandrere på Amager, efterlyser også dokumentation:

»Det er da en forfriskende og interessant tese sådan at stille det hele på hovedet, og måske finder vi en dag dokumenter, der bekræfter den. Men indtil videre har vi ikke beviser, og vi kan ikke bare overse, at der i både privilegiebrevet fra 1521 og munken Povl Helgesens samtidige smædeskrift tales om ’hollændere’«.

Nederlandsk selvstyre

Men hvad siger efterkommerne til, at de pludselig skulle have en fortid i det nuværende Belgien og ikke i Holland?

»Ja, det vender lidt op og ned på hele vores historie. Vi må jo holde os til facts, og hvis de viser noget andet, end vi hele tiden har troet, så er det jo ikke til at lave om på«, siger Lisbeth Møller, der både er født Dirksen og formand for Amager Museumsforening.

»Det lyder jo sandsynligt, at de blev hentet der, hvor man var gode til grøntsager, og ikke til kvæg«.

Museumsforeningen har inviteret Lis Thavlov til at holde foredrag om sin forskning 7. november, og »vi må da også have bogen oversat, selv om der næppe er det store salg i den slags«.

»Vi bliver i hvert fald nødt til at sige Nederlandene i stedet for Holland«, siger Mette Maltesen, der er født Jans og selv har forsket i den ’hollandske’ fortid.

Hun offentliggør her i efteråret en artikel om 20 familier, der 1651 flyttede til Frederiksberg for at overtage en kongelig avlsgård og levere kalve- og lammekød, smør og mælk til hoffet.

»Man holdt sig meget for sig selv i Hollænderbyen, hvor man havde selvstyre og også blev ved at tale nederlandsk. Det har selvfølgelig holdt traditionen om Holland i live, selv om det ville være mere naturligt at tale om Nederlandene«.

Skal det så hedde Belgierbyen?

Gartner Dirch Jansen Schmidt medvirkede i juni 2012 i Politiken i artiklen ’De har holdt med Holland i 500 år’. Han sagde dengang, at han ’har en særlig veneration for arven’, men den nye forskning vælter ikke hans verden:

»Det er klart, at den store gruppe indvandrere ikke kan komme fra samme by, og Christian II har sikkert også ledt efter de mest foretagsomme. Så det er sikkert rigtigt at tale om Nederlandene. Det har jeg ingen problemer med«, siger han.

Lis Thavlov, skal man så døbe Hollænderbyen om til Belgierbyen?

»Nej da. Den traditionelle opfattelse af indvandringen skal ikke skrives ud af historien. Den skal bare ikke hindre os i at forsøge at nuancere historien med de muligheder, vi har i dag. Vi kan jo bl.a. se, at man hele tiden har taget udgangspunkt i de lokale traditioner som navneskikke, sprog, amagerdragten og fastelavn og set dem som ’beviser’ for, at Waterland var oprindelsesstedet. Sagen er bare, at vi kan genfinde de samme traditioner i Flandern. Der kan vi jo så fortælle en ny historie«.

Kilde: http://politiken.dk/kultur/ECE2051154/forskere-amagers-hollaendere-kom-i-virkeligheden-fra-belgien/

Excerpt from the church record book (KB 1770-1811, Store Magleby, Sokkelund, København, image 107):

“Efter at der i 296 Aar er blevet prædiket tÿdsk, nemlig fra 1515 da Hollænderne kom her ind i Danmark under Kong Christian den anden, og indlod sig her i Storemaglebye, som efter ? ? blev kaldt Hollænderbye, og hvor jeg i 25 Aar har forrettet mit Embede i det nederlandske Sprog ? ? Søndag, og den anden Søndag blev dansk prædiket…”(… the last 296 years having preached in the German language, namely from 1515 when the Dutch arrived here in Denmark during King Christian 2.’s reign, and settled here in Storemaglebye, which after ? ? was called Hollænderbye, and where I for 25 years have fulfilled my office in the Netherlandic language ? ? Sunday, and the next Sunday in the Danish…)